Opinion: Sinixt Hunting Rights decision has potential for wider impact

By Karl Hele

Ruling in March 2017, that a member of the ‘extinct’ Sinixt First Nation has existing Indigenous rights to hunt, a judge in Nelson, British Columbia may have issued the first decision that will eventually upend more than a century of Canadian border policies. These policies, formulated decades before Confederation, hold that American Indians have no claims on the Canadian state nor claims to Indigenous or treaty rights even though the international border bisects many Indigenous communities from coast-to-coast. While the ruling in favour of the Sinixit is applicable only in B.C., the decision has national implications.

Approximately 60 years ago, Canada declared that the Sinixt band ceased to exist under the Indian Act. While the ‘extinction’ of First Nations’ bands under the Indian Act remains a possibility, the Sinixt became ‘extinct’ in 1956 after they had relocated across the international border. Yet, as a people, the Sinixt continued to ‘exist,’ just not in Canada. When authorities arrested and charged Richard Desautel in 2010 for hunting violations in B.C., he rejected his ‘extinction’ and challenged the constitutionality of the charges. In 2017, a B.C. judge agreed that Desautel was merely exercising his Indigenous rights. This ruling allows the U.S. resident Sinixt to hunt on their lands within Canada. If both B.C. and Canada appeal the ruling, it is likely that the issue will eventually be heard by the Supreme Court, which then has the potential to recognize an existing right for all border First Nations under section 35 of the Canadian Constitution.

First Nations in Canada living along the international border tend to claim rights under the Jay Treaty of 1792 to cross the border freely—this claim Canada has rejected for decades. In 2001, the Supreme Court of Canada agreed with the denial of the Jay Treaty claims when it rejected the Mohawks of Akwesasne’s claims to cross-border rights in the Mitchell decision. Although the ruling does not recognize the Indigenous right to freely cross the border, the Desautel decision does appear to recognize a cross-border Indigenous right under the Constitution. This possible existing s.35 Indigenous right could present First Nations whose lands were artificially divided by the international border and living in the U.S. an opportunity to engage in Indigenous resource harvesting in Canada.

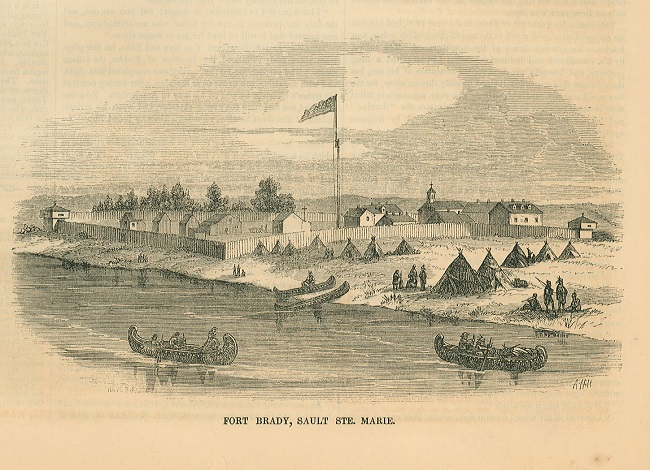

While First Nations’ rights under the Jay Treaty are rejected by Canada, First Nations with treaties need to utilize these documents to assert broader border rights under s.35. The Anishinaabeg of the Great Lakes, for instance, live astride the international border. In Sault Ste. Marie, the Anishinaabeg are divided across four bands or tribes, two in the U.S., and two in Canada. Back in 1850, the colony of Canada West entered into two treaties with the Anishinaabeg of the northern shores of Lakes Superior and Huron. While the documents and implementation of the terms of the 1850 treaties remain contested, no one appears to have yet considered the implications of who negotiated and signed these documents. For instance, a Justice of Peace from the U.S., George Johnston, acted as an interpreter and signatory, while the head government negotiator, William Robinson, resided in a U.S. hotel. American military personnel were even present at the signing in British-Canada. More importantly, one of the signatures on the treaty documents belonged to Oshawanoo, the Anishinaabeg head chief for those resident in the U.S. Oshawanoo was not the only U.S. resident Indian to sign a treaty with Canada West, only the highest ranking. Under the 1850 treaties’ terms, the Crown promised the Anishinaabeg, Oshawanoo included, that they could hunt and fish as “they have heretofore been in the habit of doing.” I suspect that the potential outcome of the Desautel decision will impact the interpretation of treaty rights in this case as well as many others.

Perhaps other First Nations along the US-Canada border need to become involved in the fight for Indigenous and treaty border rights, outside of the Jay Treaty claims. More specifically, can Indigenous individuals from the U.S. be found who are willing to be charged for hunting violations, whose defense will be the exercising of treaty or Indigenous rights? Or, will other Nations seek to become interveners in this important case. Nonetheless, by seeking to enforce our treaties, Canada will need to reconsider the rights of those Nations that span the international border. Prime Minister Trudeau, the provinces, and Indigenous (aka Indian) Affairs should move toward recognition of cross-border rights.