Indigenous children’s book celebrates book launch, three-year partnership and sacred medicine

By Laura Young

SUDBURY—In an era where smoking and tobacco are seen as vile, it’s sometimes lost that tobacco is actually a sacred medicine in Anishinabek culture.

This is precisely the point of This is my Tobacco, a children’s book that was launched on Thursday, March 22 at the Shkagamik-Kwe Community Centre in downtown Sudbury.

The book is one of several projects that has emerged from a partnership between Shkagamik-Kwe and Public Health Sudbury & Districts (formerly the Sudbury & District Health Unit). The three-year project is communicating knowledge on the traditional teachings of the sacred tobacco.

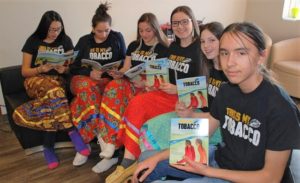

The authors Hope Osawamick, 13, her cousin Lilly-Anna, 13, Logan Daviau, 15, sisters Page, 16, and Anik Chartrand, 13, and Braeden Manitowabi-Peltier, 15, wrote the stories and drew the artwork for the book. They worked with Hilda Nadjiwan, one of Shkagamik-Kwe’s Elders, on the translation into Ojibway and on the teachings.

Manitowabi-Peltier wrote about tobacco and hunting because it’s the man’s role in life to be the providers, he said. “I learned even more about tobacco and hunting and how they are connected. It’s pretty cool [to see it in print].”

The project started meeting as youth partners in the community. K.C. Rautiainen, a registered nurse at PHS&D, was looking to do a project with Smoke Free Ontario funds. She and Teresa McGregor, Shkagamik-Kwe’s youth co-ordinator, connected and decided to gather some local young people. They recruited six youth.

“When it was offered, it was work with Indigenous youth on tobacco. I threw it out there to the powers that be that I would love it to be on safe tobacco,” McGregor says. “I didn’t think that was out there as much as ‘thou shalt not smoke’.”

The plan started with new posters that do not carry the typical ‘don’t smoke’ message. The students have created posters that reflect on how they use their sacred tobacco. They didn’t want to quit working so they then spent another year creating the book, with translation into Ojibway and French, as well as making their own artwork.

The target audience is Kindergarten to Grade Three, but the hope is that the book will be shared between all age groups and generations. They wanted to target Indigenous and non-Indigenous readers, said Rautiainen.

The book doesn’t signal the end of the project.

“We actually talked about the possibilities of the youth reading the story, acting it out. Once people found out that this book was being done, they wanted to know if the youth would go into the schools and read to the class,” McGregor says.

“What’s so amazing is that year after year, we thought this project would last one year. Now here we are in year three. It’s not us driving us, it’s them [the youth]. ”

At the launch on March 22, Angela Recollect, Shkagamik-Kwe’s executive director, said it was “absolutely critical” for organizations in the community to work together.

For too long, people have worked in silos and not shared their expertise, she said, instead she praised the model of cooperation between Shkagamik-Kwe and PHSD on this project.

The health unit printed 1,000 copies, 600 in English and 300 in French, with the remainder in Ojibway. The books are being distributed in the four school boards in Sudbury, child care centres, and other community partners, as well as in other parts of Ontario, said Rautiainen.