Four Nations Alliance Belt: A lesson in Indigenous Diplomacy

By Laurie E. Leclair

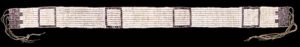

The “Four Nations Alliance Belt” can be found in the Pitt Rivers Museum, Oxford England under the accession number 1896.7.1. It is attributed to the North East Woodlands Wendat and made up of shell beads, string, animal hide and other unknown materials. Not counting its fringe the belt is nearly a meter long and 86 mm wide. The date of its creation is estimated to be between 1710 and 1720.

Here is its story:

On August 4, 1701, the Haudenosaunee Confederacy and the Anishinabek Nation forged an agreement more commonly known as the Great Peace of Montreal. Over 1,300 delegates and their families bore witness to the proceedings and when their headmen placed their totems on the treaty parchment a relative peace descended over a large part of what would become Ontario, Quebec and portions of the American northeast and northwest.

Decades prior to the treaty, the Hurons, Odawas, Ojibwas and Pottawatamies had formed an alliance with the French, one that extended over much of the Great Lakes and grew as the French trade networks expanded. The Great Peace allowed the European nation to establish a fort on the Detroit River, an important link between lakes Erie and St. Clair. Lamonthe Cadillac, the former commander at Michilimackinac believed that from the vantage point of Detroit, the French could have a better control over trade and more immediate communication with its Indigenous allies.

Following the peace, the Detroit area became temporarily safe for communities to re-establish themselves, something much desired by Cadillac who understood that his fort could not exist without the support of France’s Indigenous allies. The Huron-Wyandottes were one of the first groups encouraged to relocate to the area, joining Anishinabek villages that were either long-established in the area or created after the peace.

But if an easier access to the European market appealed to local Indigenous groups, it was equally attractive to other Northwestern nations like the Kickapoo, Winnebago and Fox who wanted control over a potential French-Sioux trade network. In early 1712, the Fox built a fort threateningly close to Fort Pontchartrain and began to attack. It was only through the intervention of warriors from the Three Fires Confederacy that the outmanned Huron-Wyandottes and the French were able to hold their settlements. The siege lasted nearly three weeks and cost the aggressors 1,000 lives.

Strengthened by victory, the Ojibwa, Ottawa, Pottawatomi together with the Huron-Wyandottes entered into a formal union. The Four Nation Alliance belt remains the only tangible evidence that such a grand council occurred, and most historians place its origin between 1712 and 1720. Over time, the belt was entrusted to Adam Brown, an adopted Huron-Wyandotte. Brown passed the knowledge inherent in the belt to his sons. It is through his grandson, Peter Dooyentate Clarke, that we learn more details about the agreement, and begin to get a sense of what the wampum recitation might have sounded like. In his history, written over 150 years after the creation of the belt, he recalled:

…about this time the four nations (the French being a fifth party) of Indians having already formed an alliance for their mutual protection against the incursions of the roving savages of the West, the four nations now entered into an arrangement about their country as follows:

The Wyandottes to occupy and take charge of the regions from the River Thames, north, to the shores of Lake Erie south. The Chippewas to hold the regions from the Thames to the shores of Lake Huron, and beyond. The Ottawas to occupy and take charge of the county from Detroit to the confluence of Lake Huron, with St. Clair River, thence north-west to Michilimackinac and all around there. And the Potawatamies the regions south and west of Detroit. … But it was understood among them, at the same time that each of the four nations should have the privilege of hunting in one another’s territory….

The belt remained with Adam Brown at Brownstown, Michigan and sometime during the late 1790s, the Wyandotte Head Chief called a council at Brown’s home. Dooyentate’s further recollections help us understand how wampum knowledge was disseminated. Here, the Head Chief, or Sastaretsi, asked Brown to take out each of the wampums and their associated parchments after which he commenced to recite the meaning of each in front of the assembly. The individuals who were charged with remembering the belts were asked to repeat the words back to Sastaretsi, who in turn corrected them if needed. Unfortunately, the Sastaretsi remained unnamed in Dooyentate’s story, but he is said to have passed away sometime between 1790 and 1801. From this, it is compelling to suggest that the recitation and repetition of wampum may have been one of the last duties of a head chief. As the great chief spoke, Brown took notes in the form of a short label affixed to each of the wampums. Over time, these labels have disappeared.

The wampum belts stayed in Brownstown until 1812 when the Huron-Wyandotte council fire moved across the Detroit River to their reserve in Anderdon Township. Here the entire Wyandotte archives remained until the nation broke up in 1842.

In 1872, the Canadian ethnologist Horatio Hale met with Wyandotte chief Joseph White and interpreter Alexander Clark at their reserve in Anderdon Township. White recalled that prior to this 1842 partition, the archives was kept in a large trunk and when taken and spread out could cover a 15-foot square room. The group that left for the United States took away the majority of the belts, leaving only those that related to the title of lands in Canada, or affairs related to their church. By the time Hale interviewed these men, the Huron-Wyandottes had only four belts in their possession, including the Four Nations Alliance Belt, all of which he purchased.

Hale collected the belt in either 1872 or 1874. This marks the first time it was photographed and described in detail. Hale noted, albeit with his cultural biases:

It was mainly a treaty respecting lands, which will account for the shape of the figures. In lieu of the oval council hearth we have four squares… which indicate in the Indian hieroglyphic system, either towns or tribes with their territories, and remind us of a similar Chinese character which represents the word field… The White-peoples houses, at the ends of the belt…signified the French forts of settlements which protected the native tribes alike against their persistent Iroquois enemies, and against the marauding Indians of the South and west.

According to Hale, and apparently supported by Chief Joseph White, the agreement remained in force until the implementation of the major land cessions enforced by Sir Francis Bond Head in 1836. While today’s scholars would certainly question this opinion, it creates a conversation around the possibility that the validity or efficacy of certain wampum belts may have had an expiration date. If this is the case, it helps us understand why Chief White was willing to part with it.

Timing was also important. Hale visited the Anderdon reserve when it was facing many challenges. In 1869, the Canadian government had just introduced amendments to its Enfranchisement Act making it possible for entire groups to enfranchise en mass. In 1873, between Hale’s visits, the Huron-Wyandotte council met several times to discuss whether its people were willing to give up official “Indian” status, convert their reserve lands to fee simple and receive a per capita cash out of their trust funds. Also during the same year, the 75-member nation agreed to subdivide its land, selling surplus lots off for its benefit. Understandably, given the weight of the decisions lying ahead, the community had split into two factions with Joseph White and Alexander Clark, Hale’s two main contacts, aligning with the pro-Enfranchisement group. Historian P. Dooyentate Clark dissented and became a spokesperson for the other side.

As he was nearing the end of his life, Horatio Hale reached out to his English colleague Edward Burnett Tylor who held the title of Keeper of the University Museum at Oxford. He believed that the four wampum belts in his possession were extremely special, and placed them “among the most ancient and important Indian historical relics of America north of Mexico.” In April 1896, he confided in Tylor that he’d never considered selling them before, but as the museum would care for them properly, the curator could have them for £ 30. An agreement was reached and the four belts were sent by parcel post to Oxford University, arriving sometime in the summer 1896, just months before Hale’s death.

The Four Nation Alliance belt remains at Pitt Rivers Museum. It came back to Canada in 1988 briefly, as part of the controversial Glenbow exhibition The Spirit Sings: Artistic Traditions of Canada’s First Peoples. Here, the belt, as one of the several hundred items on display, became part of the difficult discussion over sponsorship, appropriation, preservation and ethics.

The physical journey of the belt mirrors the history of the Wyandotte as well. Forged near Detroit around 1712, the belt codified an agreement over land use and territory shared between the Huron-Wyandottes, the French and the Anishinabeg in the wake of the largest Indigenous peace treaty on record. Like many of Huron-Wyandottes themselves, the belt remained in Brownstown near Detroit for over 100 years. Following the War of 1812, many families relocated across the river to Canada, taking the wampum archives with them. In 1842, the community split up, and a large proportion moved to Kansas, but it was decided by Wyandotte record keepers that because of its relevance to Canada, the Four Nations Alliance belt should remain in Anderdon. It would stay safe on this reserve for the next 60 years. Although Elders could still read it and recount its historic importance, the belt, like the community itself, fell victim to challenging times.

A shrinking land base and the enfranchisement process changed the shape of the Wyandotte village. During this time, Chief Joseph White believed the belt to be his personal property and perhaps with the promise of its preservation, sold it to Horatio Hale. For a further 24 years, it remained in Hale’s house, located near Goderich, Ontario and then it journeyed overseas to Oxford where, except for a brief period, it has remained for 122 years.

Wampum like birch bark scrolls, rock paintings, carvings on pipes and painting on drums form part of the Anishinabek cultural legacy. Our knowledge and understanding of Indigenous law and diplomacy grows as Elders work with scholars and craftsmen to restore and preserve the meanings inherent in these treasures. Although centuries old, wampum belts, like the one discussed here, continue to educate, and with their revitalization their stories lengthen and deepen our understanding of the past and suggest new diplomatic pathways for the future.

Suggestions for Further Reading:

Bruchac, Margaret, et al. On the Wampum Trial: Restorative Research in North American Museums. https://wampumtrail.wordpress.com

Clark, P. D., Origin and Traditional History of the Wyandotts, Toronto: Hunter, Rose and Co., 1870

Corbiere, Alan Ojiig, “Their own forms of which they take the most notice”: Diplomatic metaphors and symbolism on wampum belts” in Anishinaabewin Niiwin: Four rising winds, a selection from the proceedings of the 2013 Anishinaabewin Niiwin Conference”, Corbiere, A. O, Noakewgijig Corbiere, M., McGregor, D. and Migwans, C, eds., 2014

Dunnigan, Brian Leigh. Frontier Metropolis :Picturing Early Detroit, 1701-1838. Wayne State University Press, 2001.

Havard, Gilles. The Great Peace of Montreal of 1701: French-Native Diplomacy in the Seventeenth Century. McGill Queens UP, 2001.

Leclair, Laurie. The Huron-Wyandottes of Anderdon Township: A Case Study in Native Adaption, 1701-1914. University of Windsor, MA Thesis, 1988.

Wyandotte Nation: Preserving the future of our past! https://www.wyandotte-nation.org

Laurie Leclair

Leclair Historical Research

November 1, 2018