Interpreting the interpreters: a treaty week challenge

By Laurie E. Leclair

In the nineteenth century, treaty diplomacy between the Crown and a First Nation usually followed a specific pattern: several months, maybe even a year before negotiations were to begin, imperial representatives would visit an area, meet with traders, hunters, chiefs and headmen in order to get an idea about a particular territory. Were the communities interested in making a treaty? Who were the most influential people in these communities who were also amenable or could be made amenable to negotiating a treaty? How many families fell under a leader’s scope of influence? Once all of these questions were addressed, a promise was made to return at a later date, usually during present-giving or at that part of the Anishinabek seasonal round where the majority of a community would be together.

When the time came to meet again, the negotiating First Nation encountered an entourage of Crown representatives: the Superintendent of Indian Affairs and in some cases, the Lieutenant Governor himself, a draftsman from the Surveyor General or Crown Lands, an official interpreter, local military men and possibly clergy. Together, the group negotiated the extent of the lands to fall under treaty and the type of payment the First Nations would receive. Ideally, a consensus was reached allowing the Crown to proceed to the final, official treaty. This interim accord was often recorded on paper and referred to as a provisional agreement. A provisional agreement allowed both sides to go back to their people and discuss the terms of the treaty within the privacy of their own communities. If the provisional terms met with agreement, or near agreement, the treaty could proceed to the next stage. The interim between provisional and confirmatory treaties could be as little as a few days or weeks; however, sometimes it took decades to conclude. And some treaties were never fully completed.

In theory at least, once a provisional agreement was struck, negotiators would return to finalize the terms of the formal treaty, present First Nation participants with a proper survey of the area to be covered by the treaty, exchange gifts and initial payments. This confirmatory agreement set up the treaty relationship; much like a business or a marriage contract would be negotiated between two individuals. Both sides received a written copy of the treaty and in many cases, wampum belts were either given or exchanged and pipes were smoked to reinforce the solemnity of the situation.

Superficially, the arrangement was transformed from a provisional agreement to a legally binding compact. The published volumes of Canada’s Indian Treaties and Surrenders record 483 separate treaties forged between the Crown and First Nations from the beginning of British rule in Canada to about 1912. Arguably, very few of these treaties have been met with mutual satisfaction over the years and this has given rise to hundreds of specific claims with countless amounts of money spent on researchers, lawyers, court fees, negotiators, arbitrators and others.

The dishonest nature of the Crown, and the hollowness of its promises is the simplest reason for this widespread dissatisfaction. While we cannot refute this, as First Nations, researchers and Canadians in general, we should look deeper into the problem and work harder at understanding the complex relationships that existed between treaty makers. We know that forms of Indigenous law existed at the time that each and every treaty was signed. We also believe that a treaty constitutes a partnership. It is only reasonable then to acknowledge that the written treaty only provides a portion of its history.

Whenever possible, we must seek out the Indigenous voice, but this becomes more challenging the further back in time we travel. Occasionally, the words of Chiefs and councilors have been heard and recorded through band council resolutions, letters and petitions to the Crown, but even in this case, it is rare to find a written document untainted by the hand of an Indian Agent or a missionary or even a non-Indigenous friend. Each will show the biases of culture, gender, intent and even the point in time in which the document is written. This is especially the case when we look at treaty making.

Language is often an important vehicle of culture and during the early treaties with the Anishinabek people, concepts were sometimes translated not only in Anishinaabemowin and English, but also through French and occasionally Mohawk or Huron or other Indigenous languages. Cross-cultural oversights or inaccuracies could be made, even innocently, at any point in the negotiations. As an example, the following treaty, involving three languages, shows how easily misinterpretations could occur. Once we find that errors existed, we see how necessary it is to restore the Indigenous voice to the proceedings.

In October 1818, Chiefs Musquakie, also known as Yellowhead, and Kaqueticum, whose descendants belong to Rama and Georgina Island First Nation, negotiated a provisional treaty with George III. In its official form, it is recorded as Provisional Treaty No. 18 and although the treaty concerned over 1.5 million acres laying in Simcoe, Wellington, Dufferin and parts of Grey counties, the written document contains little more than a single paragraph describing metes and bounds. Along with the Chiefs and Principal men, the treaty bears the signature of John Givins, the Superintendent of Indian Affairs and his secretary Alexander McDonell. Later, William Claus, the Deputy Superintendent General of Indian Affairs, made a copy of the treaty. Indigenous words are absent. Fortunately, evidence found within an ancient archival fonds called the Claus Family Papers [LAC, MG 19, F1, vol. 11], hold clues to understanding what the chiefs were thinking. The documents are old and as they were originally intended to be notes taken at the time of the negotiations, they are a challenge to read. But once we start deciphering the hasty script, we see that Musquakie’s words may not have been properly conveyed.

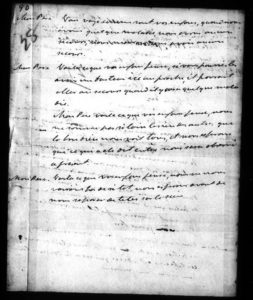

The delegation met at an inn at Holland’s Landing with representatives of the Crown, including William Gruett, an interpreter who understood Anishinaabemowin. At one point, Musquakie spoke, Gruett writing down his words in French:

Mon Père, je vous remercies de ce que vous venez de nous dire, que vous voulez faires du biens à vos enfants. Je vous remercies de ce que vous [—-] de nous dire c’est peut fait que nous autres de vous [reprendre] sur le sujet de ce que vous nous demander. [Spelling and grammar as in original]

An English officer, most likely McDonell, read through Grunt’s notes and translated the Chief’s words as follows:

Father – I thank you for what you have now said, that you intend rendering a benefit to our Children. I thank you for what you have told us, we cannot withhold a compliance with the subject of your request.

It appears from the above that Musquakie could not but agree to the proposed surrender of land. But when we do our own translation based on Grunt’s notes, the great Chief’s words are much more cautious and tentative, and quite far from consensual:

My father, I thank you for what you have just said, that you would like to do right by your Children. I would like to thank you for that which you have [–] said to us that we will resume [discussions] on the subject of which you have asked.

After agreeing to further discussions, Musquakie continued:

Mon Père, vous voye comme je suis, je me rendrai signe de pitiés, si je disais que la terres était a moy car la terre est a dieu, qui nous la donne a tous pour nous faire vivre [Spelling and grammar as in original]

In the English version the chief’s words become:

Father, It would be folly of me to say that the land is mine, for the Land belongs to God, who bestowed it on all for our subsistence.

But another, more elegant translation would read:

My father, you see me as I am, have compassion when I tell you that the land is mine only because it belonged to God, that he gave it to us all so that we could live [upon it].

Although nuanced, Musquakie’s oration conveys the belief that it was only through the Creator that he was allowed to live on the land. He asks the King to try to understand this concept. The English translation intimates that Musquakie believed it would be foolish of him to claim the land.

But after Musquakie listed his demands, in particular, his community’s need for a doctor, he clearly left the negotiations open, as recorded by Gruette:

Mon Père, voilà ce que vos enfants pense, nous ne comme pas si loin les un des autres que le bon dieu nous [voit] tous, et nous esperons que ce qui a été dit entre nous sera observé à présent.

Mon Père, voilà ce que vos enfants pense, nous ne nous voirons pas de si tôt, nous espérons avant de nous [reparer] de tétés sur le siens. [Spelling and grammar as in original]

Which the English translated as:

Father, Your Children conceive that we are not far removed from each other, but that God sees us all & we trust that the transactions which has now taken place will be adhered to. Father, your children conceive that we will not soon meet again, we therefore hope before we part to taste some of your milk.

A seasoned orator like Musquakie would have approached the discussion with much more eloquence, including a skillful use of metaphors. A second translation reflects this, as well as the idea that these were only initial talks which may lead toward a final settlement to be determined sometime in the future:

My father, this is what your children think, we are not so far away from each other, and God sees all, and we hope that what has been said today between us will be followed from now on.

My father, this is what your children think, soon we will leave and not see you, we hope that before we go we can partake of your milk.

In this translation, Musquakie is encouraging future discussions by telling Givins that his people and the Crown are close to an agreement, especially if the words, or possibly promises, made during the preliminary discussions are followed through.

The council was held October 16, 1818. The following day the Crown reported that it had secured a provisional surrender for lands:

Bounded by the district of London on the west by Lake Huron on the north, by the Penetanguishene purchase (made in 1815) on the east, by the south shore of Kempenfelt Bay, the western shore of Lake Simcoe and Cook’s Bay and the Holland River to the north-west angle of the Township of King, containing by computation one-million-five-hundred-and-ninety-two thousand acres….” [Canada, Treaty no. 18, dated 17 October 1818. Treaties and Surrenders (Fifth House Publishers, 1992), vol. 1, p. 47]

Canada, Treaties and Surrenders does not provide a record of a confirmatory treaty to the above. More historical research is needed to determine what legal steps, if any, the Crown did take to validate the alienation of these lands. But for now, this exercise should serve as a cautionary tale to all researchers: That if we rely exclusively on a written treaty, we will not understand the entire story.

Taking the French or English words, reproduced in the following appendices, and translating them back to Anishinaabemowin would be a great Treaty Week challenge for students or other interested individuals. If we can restore Musquakie’s words, we might be able to determine the extent of the liberties taken by either Gruette or McDonnell. And could this be done with other treaty council minutes? Exercises like this one help breathe life back into the treaties. Efforts to recreate and understand the voices of those Indigenous leaders who negotiated with the Crown and each other are becoming increasingly necessary if we wish to pay more than lip service to the idea that We are All Treaty People.

Appendix A:

Transcript of the October 16th Meeting from Minutes of a Council dated 16 October 1818. Daniel Claus and Family Fonds, MG 19, F1, vol. 11, folio 89-90, c-1480.

Mon Père, je vous remercies de ce que vous venez de nous dire, que vous voulez faires du biens a nos enfans. Je vous remercie de ce que vous [—-] de nous dire c’est pour fait que nous autres de vous [reprendre] sur le sujet de ce que vous nous demander. Vous voye mon Père comme je suis, je suis [signe] de pitiés quand vous arrives ou je suis comme mon feu veut mourir, aussitôt que vous ets arrives je vois un grand feu.

Mon Père, vous voye comme je suis, je me rendrai signe de pitiés, si je disais que la terres était a moy car la terre est a dieu, qui nous la donne a tous pour nous faire vivre

Mon Père Vous voye commes sont vos enfans, quand nous avons quel que maladie, nous avons aucun secour, nous mourrirs sans avoir aucun secours.

Mon Père : Voilà ce que vos enfans pense, si vous pouvés les avoirs un docteur ici ou proche Il pouvait aller au secours quand il y avoir quelque maladie.

Mon Père voilà ce que vos enfans pense, nous ne comme pas si loin les un des autres que le bon dieu nous [voit] tous, et nous espérons que ce qui a été dit entre nous sera observe a présent.

Mon Père Voilà ce que vos enfans pense, nous ne nous voirons pas de si tôt, nous espérons avant de nous [reparer] de tétés sur le siens. [Spelling and grammar as in original]

Appendix B:

Department of Indian Affairs Translation of Gruette’s Notes, Attributed to Alexander McDonnell in Minutes of a Council dated 16 October, 1818. Daniel Claus and Family Fonds, MG 19, F1, vol. 11, folios 101-103, C-1480.

Father – I thank you for what you have now said, that you intend rendering a benefit to our Children. I thank you for what you have told us, we cannot withhold a compliance with the subject of your request. Father, you see the conditions I am in I am an object of compassion, you come to the place where I am now, as my fire was on the point of being extinguished – so soon as you arrived I saw a large fire. Father, It would be folly of me to say that the land is mine, for the Land belongs to God, who bestowed it on all for our subsistence. Father, see the state of your Children, when we are afflicted with sickness, we have no one to relieve us, we die without assistance, if you [——] procure a Doctor to reside in this vicinity he might come to our assistance in the event of sickness. Father, Your Children conceive that we are not far removed from each other, but that God sees us all & we trust that the transactions which has now taken place will be adhered to. Father, your children conceive that we will not soon meet again, we therefore hope before we part to taste some of your milk…

Appendix C:

An alternative Translation [by Laurie Leclair, Union of Ontario Indians/Anishinabek Nation Researcher]

My father, I thank you for what you have just said, that you would like to do right by your Children. I would like to thank you for that which you have [—] said to us that we will resume [discussions] on the subject of which you have asked. You see, My Father, the state that I am in, I am a sorry sight. When you arrived I was like my fire, about to die out, as soon as you arrived the fire was rekindled.

My father, you see me as I am, have compassion when I tell you that the land is mine only because it belonged to God, that he gave it to us all so that we could live [upon it].

My father you see that there is sickness among your children, that we have no help and we will die without any help.

My father, this is what your children think, if you could let us have a doctor, here or nearby, it would give us help when there is sickness.

My father, this is what your children think, we are not so far away from each other, and God sees all, and we hope that what has been said today between us will be followed from now on.

My father, this is what your children think, soon we will leave and not see you, we hope that before we go we can partake of your milk.