Absurdity ad infinitum: Status and the Indian Act

In 1985, the Conservative government officially ended enfranchisement with Bill C-31 and restored Indian Status to thousands of people albeit with some serious asterisks. Some of those asterisks were removed in 2011, 2016, and 2019. Yet, more remain encoded within section 6 of the current Indian Act.

Last month, I was in court arguing against the Indian Registrar’s decision to deny my daughter registration as a Status Indian. The denial is based on the paternal grandparents, my mother’s decision to voluntary enfranchise in 1965 under the terms of section 108(1) of the 1952 Indian Act which was in force until 1985. My application to have my daughter registered was denied in 2011 and the appeal of this decision was denied in 2017. The second denial led us to court. Ironically, if my mom had lost her Status at the time of marriage, my child would be eligible for registration.

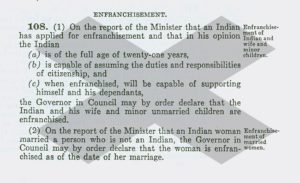

Under section 108(1), an Indian could voluntarily enfranchise provided the individual met a series of conditions such as being at least 21 years old, capable of assuming the duties of citizenship, and able to support oneself. Individuals restored to Status, who voluntarily enfranchised, were given 6(1)(d) Status under the 1985 amendments and their descendants were granted 6(2) Status. This barred a voluntary enfranchisee’s descendants, specifically the grandchildren, from being entitled to be registered. A similar logic applied to women who had married out in 1985, but subsequent court decisions forced the Government of Canada to remove those sections in 2011, 2016, and 2019. Section 6(1)(d) of the current Indian Act remains in force.

The entire notion of voluntary enfranchisement under the Indian Act is problematic. Many individuals, including my mom, found themselves pressured to enfranchise. Under section 108, married women and minor children could be enfranchised by the husband and father. These individuals, the wife and minor children, also fall under section 6(1)(d). Voluntary enfranchisement was often hardly voluntary – it was a hard decision foisted upon First Nations by a country that denies people basic human rights and equality.

In my case, following highschool, my mom became a teacher and found herself moving to different cities throughout Ontario pursuing teaching opportunities. During this period, her mother, my grandmother, began to be harassed by Garden River Band Councillors who called and visited, demanding that all her children living away from the reserve enfranchise. These individuals insisted that women who lived away would marry non-Indians and as such, these non-resident band members had to ‘sign out’ of the band by enfranchising. Mom decided that to relieve the pressure on her mother, and recognizing that marriage to a non-Indian was most likely, she signed away her Status. This is not the definition of ‘voluntary.’ My mother, her sisters, and my grandmother were being harassed and persecuted to force the enfranchisement of those individuals who did not reside on the reserve.

I sat in court listening to the Crown and my lawyers debate the reading of section 108(1) of the 1952 Indian Act. Simply, the Crown argued that the word “Indian” was to be read as both men and unmarried women. Such a reading is necessary, apparently, since the section also refers to “his wife and unmarried children” making it unnecessary to read “Indian” as including all women. Nicholas Dodd, my attorney, argued that such a reading is inappropriate, since “Indian” clearly means man or men within the context of the entire section and in reference to the definition of Indian contained earlier in the Act. Thus, from our reading, the Crown had no legal jurisdiction to grant requests for voluntary enfranchisement from unmarried women.

Interestingly, the file that would have contained my mother’s original request for enfranchisement is missing or could not be located in Indian Affairs records. Scott Robertson, the lawyer representing Aamjiwnaag First Nation as an intervener, similarly argued that the idea of voluntary enfranchisement is problematic, rests on colonial assumptions, and importantly, the entire case and others like it are contrary to the current Liberal government’s emphasis on reconciliation. Roberston also pointed out that the Government of Canada has been repeatedly told to fix ‘Status’ entitlement repeatedly by courts, commissions, and expert reports.

It can also be argued that the amendments made to the Status section of the Indian Act in 2011, if my mother’s enfranchisement is determined as valid, have created an unconstitutional discrimination based on family status against unmarried women and that this also has created unconstitutional discrimination based on gender according to section 15 of the Canadian Constitution. My solicitors did not make this argument in court; we decided to rely on a statutory interpretation of “Indian” as the determining factor. Yet this remains an option depending on the outcome of the case.

Throughout the two-day process, the complete absurdity of the idea that enfranchisement became a colonial legacy after being relegated to the dustbin of Canadian colonialism in 1985. It became readily apparent in court that the idea and process of enfranchisement was alive and well despite government assertions that various amendments had equally restored Status to all those who lost it prior to 1985. Yet 2011, 2017, and 2019 changes to the Indian Act testify to the fact that equality was not created in 1985. We sat for two days arguing that the Indian Registrar’s decision relating to my daughter in 2017 was the question before the court which was based on a misreading of a 1952 Indian Act rule that led to an unauthorized or illegal enfranchisement in 1965. Further, the 1985 changes to the Indian Act only enshrined the rules for enfranchisement created in 1952. All this leads one to conclude that the much touted ‘equality’ of section 6 of the modern Indian Act really relies on the now invalidated, rejected, repealed, and decried colonial sexist and racist notions of enfranchisement. And, none of this would matter had Status been lost at the time of marriage. Therein lies the absurdity.

It becomes ever more absurd when one considers that under the 1952 Indian Act, my mother, after voluntarily giving up her Status, could have regained her Status through marriage. Other situations of family, relationships, and Status rules add to the absurdity of the colonially created code of Status and entitlement to be registered. Why then seek registration if it is colonially encoded and maintained?

The idea of carrying a card that indicates Status, is colonialism and racism writ large. However, section 6 of the current Indian Act speaks of a person who is “entitled to be registered,” it does not matter if you as an entitled person registered or not, your descendants depending on marriage will maintain that right. If you are ‘entitled’ to be registered as an Indian, you have a set of rights or access to rights different from those who are not entitled to be registered. Additionally, being registered ensures continuance of access to lands, hunting/gathering rights, treaty rights, burial rights, educational rights, and countless other rights. Those who are not recognized as being “entitled to register” have difficulty or cannot access these rights. I am fighting for my daughter’s rights as well as other descendants of women who voluntarily enfranchised under the 1952-1985 rules. Simply, having the ‘entitlement’ to be registered is important no matter how colonial it seems because there is simply no other option until First Nations seize complete control of membership/citizenship and Canada actually treats our communities as Nations. Therein is another absurdity. The Liberal government promises Nation-to-Nation relationships yet maintains a list that is used to delineate or determine or deny rights based on criteria that is set and maintained by the very government seeking and promising reconciliation and a Nation-to-Nation relationship – colonialism is therefore maintained.