The importance of advocacy, respect and trust

By Laurie Leclair

For nearly five years, Anishinabek Nation’s Heritage and Burials Committee has been travelling across Ontario, asking its members for feedback regarding the treatment of ancestors and sacred treasures by federal and provincial governments and associated institutions. Through sharing, important groundwork was lain and in late 2019, the Anishinabek Nation summarized these discussions into its Community Heritage and Burials Consultation Protocol Template.

This first of three essays will focus on the importance of advocacy and how having an established protocol can help bring change from outside of the community. A thoughtful and viable policy on-hand will help open conversations between First Nation governments and those politicians and law-makers who are in the best positions to make substantive changes to Ontario’s policies regarding engagement.

From its very outset, the Protocol Template cultivates a spirit of cooperation by encouraging communities to build their policies around the principles of Respect and Good Faith, and Relationships and Trust.

Good relationships among First Nations, the Crown and other proponents are forged by ensuring that First Nations are involved at the very beginning of a discovery, or as stated in the protocol template, that moment when “the Crown or proponent plans or becomes aware of any decision or action that may have an impact on the First Nation’s rights and interests for our ancestors, Sacred Sites, and sacred Items.” (Protocol, 2019, p. 12) Advocacy has a better chance of success when all parties concerned are respectfully treated.

Clarity and communication are also prerequisites for successful advocacy. Many questions, both practical and profound, were raised during our research and working group discussions. For example, Brandy George, a member of Kettle & Stony Point First Nation and a licensed archaeologist, took issue with the existing legislation as it leaves her with more questions than it answers. She asked, ‘Who decides whether a First Nation community has been adequately consulted? What is the depth of this consultation? Are the appropriate people involved, are they armed with adequate and comprehensible information? Is funding in place to facilitate travel and hire expertise?” While George’s questions are aimed at those institutions that have created the existing Standards and Guidelines, Former Regional Chief Isadore Day’s inquiries went to the very essence of the science: “Why is this person being disturbed? Who is imposing this action upon us? How do we minimize the level of intrusion upon our ancestors and incorporate this challenge within a viable archaeological discourse?”

Community involvement and discussions can help a First Nation answer some of these questions. Committing this dialogue to mind or to print can shape how a group will best approach a situation. Sharing these beliefs with the Crown or with proponents encourages the latter to understand a First Nation’s needs when dealing with sacred sites. It is much easier for politicians, archaeologists and heritage specialists to empathize and even advocate for best practices once they comprehend the serious impact that a given archaeological study could have on ancestral as well as living communities.

A Case Study: Curve Lake First Nation and the Ancestors at Jacob Island

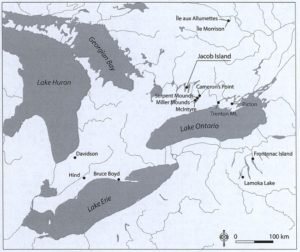

The excavations at Jacob Island in the Kawartha Lakes provide us with an example of how the principals of advocacy, respect and trust can coexist with scientific inquiry.

Cultural Archivist Anne Taylor’s experience with the Jacob Island archaeologists was a positive one and demonstrates how different groups can work together, particularly when the authority of First Nations is recognized from the beginning of a project. In 2009, an ancient burial of a woman and her baby were discovered on the island. Further examination revealed the existence of a larger burial ground a few dozen feet away. The lead archaeologist James Conolly and the land developer met on site with Ms. Taylor and members from the Curve Lake Elder Advisory Circle and together they determined how to proceed. Dr. Conolly’s published remarks on Community Engagement illustrates this process. Dr. Conolly wrote:

…after consultation with Curve Lake…all development work in this area of the island ceased … An important goal while meeting our objectives was to minimize disturbance of the burial area preferring where possible to document human remains in situ rather than excavate. This limited our ability to assess the full extent of burial patterning but, as shown here, even with this constraint we have been able to obtain considerable insight into the mortuary activities. Disturbed human remains removed during the exercise were reburied in a ceremony conducted by Curve Lake Elders in October 2011…grave offerings were returned after documentation and remain in context. (Conolly, 2014: 111)

Conolly concluded his report by noting, “Finally, Curve Lake First Nation provided community oversight and guidance during the burial documentation work, and we were honoured to have participated in the reburial ceremonies.” (Conolly, 2014:127) Following the archaeological assessment, it was revealed that the area had been used as a sacred site dating as far back as 5,000 years.

When asked to elaborate on the key to this relationship’s success, Ms. Taylor attributed it to the efforts of the Elder Advisory Circle, now known as the Cultural Advisory Circle. For her, a comprehensive consultation protocol must include Elders, in particular, Anishinaabemowin speakers. They must be involved from the time a “proponent plans or becomes aware” of a site through to the sacred task of reburial. Firstly, their knowledge and guidance will help shape a protocol unique to their First Nation. Secondly, their presence and application of ceremony and spoken language on site will help mitigate the more invasive and destructive aspects of an archeological inquiry, for both the attendees and the ancestors.

The above example shows how being proactive and prepared can result in a mutually beneficial experience for both the First Nation and the scientific community. But this example of best practices has occurred in spite of the existing laws. How could establishing protocols help to change the very ministerial legislation which controls archaeology in Ontario?

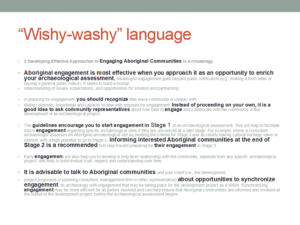

The existing legislation has failed in accommodating First Nation agency. The diagram below shows an excerpt from the Ministry of Heritage, Sport, Tourism & Culture Industries (MHSTCI), formerly Tourism Culture and Sport’s Engaging Aboriginal Communities in Archaeology Draft Technical Bulletin. Former Curve Lake First Nation Chief Phyllis Williams calls the language in the bulletin “wishy-washy”; Ms. George contends that the document “lacks teeth”. A quick glance at the bolded text at right confirms what all of the respondents in our Heritage and Burials working groups believe that the existing Standards and Guidelines is inadequate.

Although critical of the existing legislation, when Williams reflects on her First Nation’s experience with archaeologists like Dr. Conolly, she remains hopeful. Respect between archaeologists and her community has led to the creation and implementation of training programs where First Nation members work alongside archaeologists. The sharing of information when it is done in a trusting relationship will empower both groups so that, as in the case of the Jacob Island site, mutually-beneficial results can occur. The active engagement of First Nations communities in archaeological programs, to the extent that each community may wish, can build capacity and engender a certain degree of comfort on the subject. With this growing expertise on-hand, First Nations leaders can then apply informed strategies when lobbying their Members of Parliament to bring about meaningful and necessary change. Given the fact that the MHSTCI is now reviewing its current Standards and Guidelines, it is clearly time to start planning.