Ipperwash Summer Series: Reflections on the Public Inquiry: Justice Sidney Linden

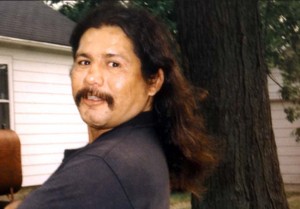

September 6, 2020, will mark the 25th anniversary of the shooting death of unarmed protestor Anthony “Dudley” George by an Ontario Provincial Police sniper at Ipperwash Beach. The Anishinabek News will feature an Ipperwash Summer Series to highlight the history, trauma, aftermath, and key recommendations from the 2007 Report of the Ipperwash Inquiry. First Nations in Ontario understood that the Inquiry would not provide all of the answers or solutions, but would be a step forward in building a respectful government-to-government relationship.

For information on the 2007 Report of the Ipperwash Inquiry, please visit: http://www.attorneygeneral.jus.gov.on.ca/inquiries/ipperwash/closing_submissions/index.html

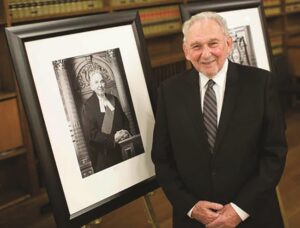

Reflections on the Public Inquiry: Justice Sidney Linden, head of The Ipperwash Inquiry, looks back on the tragic events of 25 years ago, in discussion with now-retired Toronto Star reporter Harold Levy, who, along with his colleague Peter Edwards, helped bring those events to light.

By Harold Levy

On May 31, 2007, the day Commissioner Sidney B. Linden released his report on the Ipperwash Inquiry. Dudley George’s older brother, the late Maynard ‘Sam’ George, gave Linden a compliment which Justice Linden treasures to this day, praising the Inquiry’s findings to the CBC as, a “huge and wise step forward for natives and non-natives together,” and adding, “I hope it is as good for you as it is for us today.”

The compliment was deeply meaningful for Linden, because as Peter Edwards wrote in his seminal 2001 book, One Dead Indian: The Premier, The Police, and The Ipperwash Crisis, “Sam and his family wanted to be able to believe the police and the government, but they would rest easier if they were given believable explanations for what happened that awful night of September 6, 2005.”

“Hours after the shooting, shortly after he saw his brother Dudley stretched out dead at Strathroy Middlesex Hospital, Sam George said he needed answers about what happened that night,” Peter Edwards continued. “His voice was soft and he wasn’t accusing anyone of anything. He just needed answers. More than six years had passed, and Sam George is still waiting for the answers.”

Justice Linden had clearly provided Sam with those long-awaited answers.

“Sam George’s support did not come easily, it had to be earned,” Linden told me. “Every day, Sam sat right in front of me in the front row, sending me a clear message that he expected this to be a real inquiry and not just a sham. Initially, I had the distinct impression that Sam was skeptical about the process, as many were, but as the hearing progressed I could tell that his skepticism was eroding, that he realized that we were not there to whitewash it – and that we were there to get the truth.”

UNCOVERING THE TRUTH OF IPPERWASH:

Premier Dalton McGuinty had given Justice Linden a two-fold mandate: The first part of that mandate was to inquire and report on events surrounding the death of Dudley George, who was shot in 1995 during a protest by First Nations representatives at Ipperwash Provincial Park and later died.

His job, as Justice Linden explained in the introduction to the Report, was “to uncover the truth” of Dudley George’s death “to find out what happened – to look back.”

With the perspective of time, it is also evident that that is exactly what he did.

As Journalism Professor John Miller concluded in his study of media reports on Ipperwash (most of them buying the official police and government line that the protesters, armed with guns had precipitated the conflict), the Inquiry had helped establish, “the true facts of what had happened” and that “it is now accepted that the First Nations protesters were not armed and that a burial ground did exist in the provincial park.”

The importance of Justice Linden’s unrelenting pursuit of the truth cannot be stressed enough: It meant that in the aftermath of the Inquiry, the official lies and distortions, aggravated by the one-sided nature of much of the reporting, had been finally put to rest.

It also made clear to the world that Dudley George was not the lawless, armed desperado that the government and the police had portrayed him. And that the men, women and children (grandparents among them) accompanying him, the targets of police dogs and tear gas [many of them wrongfully charged by the Ontario Provincial Police (OPP) with criminal acts that nightmarish evening], were engaged in lawful protest over the desecration of their ancestral burial grounds.

Moreover, the Inquiry gave its findings even more strength by placing them in the context of the weight of decades of discrimination and dispossession, the oppressive history of government policies that had harmed the long-term interests of First Nations People, and the ugly currents of racism that stained the police and government responses to the protest.

The inquiry also affirmed beyond any doubt (not that there should have been any) that the lands in question belonged to the First Nations People and it recommended that these lands be returned to them as soon as possible – even though technically this was a federal matter and therefore outside of its mandate.

“One of my biggest concerns as Commissioner, was that after taking ten years to get to the point where the Inquiry was up and running, people would react negatively saying ‘Where was the value? We knew this already.’” Justice Linden said. “To the contrary, as the inquiry progressed, I began to get positive feedback that we had made a connection, that the information and truths we were unearthing had brought something tangible and lasting to the First Nations community. That was gratifying.”

“I was also concerned with the idea of facing rows of lawyers representing the 17 parties to whom I had granted status to participate,” Linden adds. “That concern also proved to be unfounded as most of the lawyers appreciated the historical nature and purpose of the Inquiry and went beyond their duty to represent their individual clients and helped to make the inquiry work… Indeed, not one of them used the recourse available to them to appeal any of my decisions to the Divisional Court, which would have prolonged the Inquiry.”

PREVENTING FURTHER AVOIDABLE TRAGEDIES:

With the perspective of time, it is also evident that Justice Linden made valuable recommendations for preventing avoidable tragedies such as Ipperwash – the second part of his mandate.

As the University of New Brunswick sociologist Professor Tia Dafnos noted in her Ipperwash article with the Anishinabek News, “The Ipperwash Inquiry remains one of the only official inquiries in Canada to address the policing of Indigenous struggles; its findings and recommendations were directed at the OPP but reverberated widely in policing.”

Professor Dafnos added that many of Justice Linden’s specific operational recommendations – such as that police should address the “uniqueness” of Indigenous “occupations and protests” including their “historical, legal and behavioural differences” – became critical policies of the OPP.

Justice Linden, an avid sports fan, says that as the Inquiry progressed, it became apparent that policing an Indigenous protest (for which an understanding of Indigenous history and culture was crucial), was very different from having to police an unruly soccer crowd.

“During the Inquiry, each of the officers who had marched down East Parkway Drive in riot gear with helmets, shields, batons and guns were asked whether they had any previous knowledge of Aboriginal issues,” he added. “It was upsetting that not one of them did.”

“Tragically,” Justice Linden says, “They were just a group of young police officers who had not been trained for what they were being asked to do. They had no notion as to what the underlying dispute was and as to the reason why these men, women and children were occupying the park. And the politicians, with their narrow political objectives of appearing tough and quickly ending the dispute, were not seeking the independent, objective advice which could have avoided the chaos and violence leading to Dudley George’s death.

“If the OPP officers at Ipperwash had understood that history and culture, and if First Nation’s police services had been used, they would have understood that the [Indigenous] occupiers were not like a soccer crowd and instead of a show of force, they would likely have resorted to mediation and other non-violent alternative approaches [as recommended by the Inquiry].”

Also in the ambit of policing, one of the most significant issues Justice Linden had to tackle was the allegation that political interference with OPP operations and decision-making was a factor in Dudley George’s tragic death – an allegation which he ruled was unfounded.

In the succinct words of the Report: “The provincial government had the authority to establish policing policy, but not to direct police operations. The Premier and his Government did not cross this line. There is no evidence to suggest that either the Premier or his government directed the OPP to march down the road towards Ipperwash Provincial Park, on the evening of September 6.”

However, The Report added that “This is not to say that the interaction between the police and government at Ipperwash was proper or conducive to a peaceful resolution. There was a considerable lack of understanding about the appropriate relationship between police and government.”

Looking back, Justice Linden attributes this lack of understanding of the police/government relationship to the reality that around September 6, 1995, the Mike Harris Government had only been recently elected and the Premier and his staff knew very little about Indigenous issues.

“The Premier and his officials thought that it was a simple matter of trespassing on government property,” he said. “Harris just wanted to get the Indians out of the park. He didn’t understand the history and he made no or little attempt to learn about Aboriginal history and culture, or to understand the attachment of the First Nations people to their land.”

Looking ahead, in order to ensure police accountability, Justice Linden recommended a ‘democratic policing model’. A model in which police had absolute authority over operational decisions such as who should be investigated, arrested and/or charged— and in which government was charged with the responsibility of setting clear and transparent policies for the police on issues such as how to respond to land claim disputes.

It was a ‘peace-keeping’ approach aimed at facilitating constitutional rights and the building of constructive relations, in which force was to be used only as a last resort.

Justice Linden later found support for his democratic policing model from an unlikely source, my friend, the late celebrated National Post columnist Christie Blatchford, an unabashed police supporter.

In her 2010 book, Helpless: Caledonia’s Nightmare of Fear and Anarchy, and How the Law Failed All of Us, Christie applauded his championing of ‘democratic policing’ over ‘police independence’ and wrote that “[a] more intelligent and sympathetic view of aboriginal and Canadian history [than the Ipperwash Inquiry Report] would be hard to find.”

HELPING HEAL A WOUNDED COMMUNITY:

In our discussions, Justice Linden made clear that he took a wider view of his role than just fulfilling his mandate.

“That’s true,” he says. “I set out to conduct this inquiry in a way that would help heal a wounded community that had experienced decades of violence, bitterness and division.”

To that end, he decided to give the occupiers an opportunity to take the witness stand and to talk publicly to an impartial commission charged with ascertaining the truth of what had happened about their ties to the land, their reverence for their ancestors, and their aspirations for their children.

“At the outset, I was rather worried that I would be harming this community by opening up old wounds,” Linden adds. “But this was anything but the case. It was as if they had been waiting for years for the opportunity to be heard.”

Justice Linden also sought healing through ‘history’ by calling expert witnesses to testify as to the long history of protest by the Kettle Point and Stoney Point communities before the occupation of the park – as that history was vital to understanding Ipperwash and the death of Dudley George.

Other steps Justice Linden took to reach out to the community included:

- The decision to hold the Inquiry in Forest, Ontario, in the community centre near the Park, gave the people who were most affected by its deliberations the opportunity to feel comfortable and participate.

- His visit to the park, together with his Senior Counsel, Derry Miller – during which he had the opportunity to meet with Sam George, and to begin building up trust and confidence in the Inquiry.

- A formal session that was held with many young people in the area helped the Inquiry get a sense of their attitudes towards the Ontario Provincial Police.

- And most importantly, respect would be shown to the Indigenous customs and traditions throughout the Inquiry through invocations by Indigenous leaders, smudging, drumming ceremonies and using an Eagle Feather while testifying.

Justice Linden’s ultimate success in instilling a healing process through the Inquiry was evidenced in a Sarnia Observer editorial that read, in part: “The Ipperwash inquiry, which had the potential to do great harm to race relations in the north end of Lambton County, ended on a high note Tuesday. And the credit for that rests almost entirely with Justice Sidney Linden.”

“From the outset, Justice Linden made it clear that one of his objectives was to bring a sense of healing to a community that had been wounded in more ways than one by the bloody confrontation between police and natives at the former Ipperwash ‘Provincial Park’,” the editorial continued. “He said he wanted to do more than just investigate the circumstances surrounding the September 6, 1995 incident. He wanted to leave the community a better place than when he found it.”

LOOKING BACK: WITH THE PERSPECTIVE OF TIME:

Twenty-five years after Dudley George was killed in the misguided OPP operation that fatal evening, Justice Linden still exudes admiration for the man, and for the people whom he inspired to reclaim their land.

“He was a hero to his people, a young, good-natured idealist who gave his life for a principle he believed was important,” says Linden. “His community was rightfully outraged by the police and government efforts to destroy his reputation – to turn him into a ruffian out to steal land and harm the police. As a result of the Inquiry, his reputation was restored beyond question.”

The last word to Justice Linden before this article adjourns.

“It’s good that we are still talking about Ipperwash – there is so much that another generation can learn from it – and I hope that the sacrifices made by Dudley George and his courageous supporters will never be forgotten,” Justice Linden says. “And we can only hope that we never have another Ipperwash in Ontario, or anything like it anywhere in Canada.”

Harold Levy is now retired from the Toronto Star where he reported on criminal justice for many years. He also practiced criminal law in Ontario’s courts.