The Clench defalcation specific claim settlement

By Laurie Leclair

In 1845, Canada, or rather Upper Canada, appointed 55-year old Joseph Brant Clench, a militia officer and life-long Indian Department employee, as head of the department’s land sales for the London and Western Districts. At the same time, he controlled the Western Superintendency and was the acting Superintendent for the Grand River. He dabbled in local politics as well, and until 1848, had the role of inspector of taverns, shops and stills for London district.

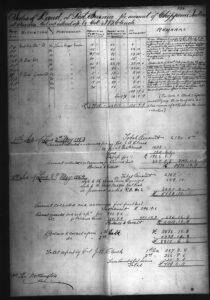

As part of his lands duties, Clench was responsible for all the revenue coming from the sale of Anishinabek territory in southwestern Ontario, including that of Bkejwanong, Aamjiwnaang, Kettle and Stony Point and the Chippewas of the Thames. As the monies came directly to his home, his job was to make sure that the correct sums were deposited into the appropriate trust funds. At the time Kettle Point, Stoney Point and Aamjiwnaang shared the same account, known as The Chippewas of Sarnia, or Trust Fund no. 5.

By the early 1850s, Clench had discovered that his wife Esther Serena and his sons Leon and Holcroft were stealing money intended for First Nation Trust funds, and soon after, Clench’s inability to perform his duties as Indian Agent became clear to the Department. In 1854, it sent in inspectors Thomas Worthington and C. E. Anderson, who, after reviewing Clench’s files, recommended that he be suspended. The Superintendent was taken to court where it was discovered that his family had appropriated an estimated £9,000 meant to be deposited into Anishinabek accounts. After the trial, Clench, now estranged from his family, left London and retired to Caradoc Township where he died two years later, still heavily indebted to the Indian Department.

For decades, the Anishinabek communities of Southwestern Ontario and the Canadian government have had to deal with resolving these issues. Clench’s embezzlements and breaches of trust, or defalcations as they are known, have touched every Indigenous community in southwestern Ontario. This autumn, the people at Kettle and Stony Point and Aamjiwnaang will be faced with a very important decision. They have been asked to consider a final settlement agreement for misappropriated funds stemming from the sale of a portion of land taken from the southwestern corner of Aamjiwnaang. The sale of this property, a small area of river-frontage, had been put up for auction in a Sarnia public house. Only a portion of the money generated from the sale found its way into Trust Account no. 5. According to Aamjiwnaang First Nation Chief Christopher Plain, since some of the revenue was recovered from the Clench estate in 1907, the settlement being voted upon represents the balance of the funds owed.

Kettle and Stony Point and Aamjiwnaang First Nations entered into a joint-specific claim over this land and in 2015, Canada offered a global settlement to “fully and finally settle the Clench claim with both communities.” Both communities, however, had to determine how the money would be apportioned between the two. On May 31, 2019, after lengthy mediations, the two groups decided on a 52/48 per cent split, giving an estimated $18, 513,445 to Aamjiwnaang and $17,214, 909 to Kettle and Stony Point. In order to ratify this agreement, members from both First Nations must consent to this division and agree to the terms.

On September 8, Aamjiwnaang posted its notice of ratification and will hold its vote on October 9, 2020. Prior to that, it will be conducting community information sessions on September 22 and 23.

Kettle and Stony Point First Nation Chief Jason Henry discussed the history of the claim and the process of ratification in a Facebook message to his community on August 19. The community vote is set for November 13.