Canada’s reckoning with colonialism and education must include Indian Day Schools

Trigger warning: readers may be triggered by the recount of Indian Residential Schools. To access a 24-hour National Crisis Line, call: 1-866-925-4419. Community Assistance Program (CAP) can be accessed for citizens of the Anishinabek Nation: 1-800-663-1142.

Previously published on theconversation.com on July 12, 2022.

By Sean Carleton and Jackson Pind

Sparked by the locating of hundreds of possible unmarked graves at former Indian Residential Schools across the country, there has been a public reckoning with the ongoing legacies of the Indian Residential School system.

Many Canadians are finally coming to terms with the truth that the Canadian government, in co-operation with Christian churches, ran a genocidal school system intended to “kill the Indian in the child” for more than a century.

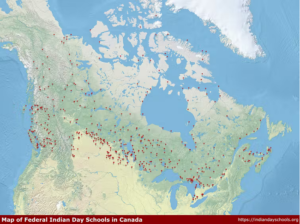

What most people don’t realize, however, is that Canada’s system of “Indian education” was not limited to Residential Schools. It also included a vast network of nearly 700 federally funded and church-run Indian Day Schools, which were attended by an estimated 200,000 Indigenous people between 1870 and 2000.

Despite making up a large part of Canada’s system of Indian education, Day Schools were excluded from the Indian Residential Schools Settlement Agreement. A different class action for day schools recently closed on July 13, 2022, and so far, over 150,000 people have been included.

In recognition of the brave Survivors who have been fighting for justice and sharing their stories, we argue that Canada’s reckoning with colonialism and education must also include Indian Day Schools. If Canada is serious about putting truth before reconciliation, then the history and ongoing legacies of all kinds of colonial schooling need to be acknowledged and addressed.

The history

Day School and Indian Residential School systems need to be understood as interrelated and overlapping parts of Canada’s assimilationist education project.

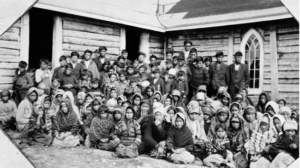

In the mid-to-late 1700s and early 1800s, Christian missionaries started schools for Indigenous people — most without financial support from government — in an effort to gain converts and control.

By the 1870s, the federal government had officially partnered with churches and offered to pay more for schooling as a way of gaining greater influence and authority over Indigenous peoples.

The new system of Indian education, overseen by the Department of Indian Affairs, had two distinct prongs: Day Schools, which were often located on reserves where children could return home at the end of the day, and boarding or “Residential” Schools, where children resided at schools far away from their communities — sometimes children attended both, at different times, during their school years.

The two kinds of schools shared the same goal: to solve the so-called “Indian problem” by undercutting and delegitimizing Indigenous ways of life to better facilitate settler capitalism and Canadian nation-building.

The Day School system lasted until 2000 with the Anglican, Roman Catholic, Presbyterian, Methodist and, later, United churches overseeing daily operations of the schools in various parts of the country.

Like at Indian Residential Schools, news stories have also reported deaths, experiments, and abuse at Day Schools that have had lasting impacts.

The reckoning

For more than a decade, Day School Survivors have been fighting for truth and justice. Since the settlement was reached in 2019, both of the original settlements’ founders Garry Mclean and Raymond Mason, have passed away.

The Mclean Day School Settlement Corporation was established with a $200 million legacy fund that emerged from the settlement with the federal government and is intended to support “language & culture, healing & wellness, commemoration and truth telling.” The settlement process has had mixed results so far.

Journalist Ka’nhehsí:io Deer found that Survivors have been revictimized by the process and that 85 per cent of the claims that were settled occurred at Level 1 (the lowest amount available, $10,000).

While over 150,000 Survivors submitted an application, others repeatedly asked for more time to tell their stories.

The recent federal budget saw the government earmark $25 million between 2023 and 2025 for Library and Archives of Canada to “support the digitization of millions of documents relating to the federal Indian Day School System, which will ensure survivors and all Canadians have meaningful access to them.”

This funding is important, but it will come too late to help Survivors with the class action.

Digitization efforts are important because they can generate more awareness and education about the Day School system. This is significant because, unlike the Truth and Reconciliation Commission (TRC), there will be no national inquiry or final report.

Murray Sinclair, chair of the TRC, often says that education got us into this mess so education must get us out.

As part of this process then, people must learn more about the history and legacies of Indian Residential Schools and day schools (and public schools, too) and understand their relationship to Canada’s colonial project.

We encourage readers to check out www.indiandayschools.org to find the Indian Day School closest to them and read more about this history.