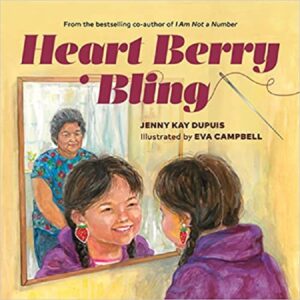

Jenny Kay Dupuis celebrates Indigenous joy with new book

By Kelly Anne Smith

TORONTO- The new book, Heart Berry Bling, teaches Indigenous realities and culture while warming the human heart.

Jenny Kay Dupuis brings her new children’s book to life, written with 6 to 8-year-olds in mind. Anyone of any age will feel the joy in the relationship of Maggie and Granny, as Maggie learns to bead.

An influential Indigenous author, Jenny Kay Dupuis of Nipissing First Nation, shows sensitivity to Indigenous trauma, involving the principle of ‘do no more harm’, according to the Elements of Indigenous Style Guide. In conversation, Dupuis talked about spaces she entered in, both in school and in public libraries, when she was growing up as a kid.

“There weren’t really any Indigenous books that I could see for children at the time or that were made available on the shelves.”

Now, Dupuis sees representation and opportunity where there are Indigenous authors writing Indigenous stories. Dupuis chooses stories that share truth.

“Truth based on helping people explore understandings or build understandings when it comes to those policies that took so much away from our communities over the years – took us away from our communities, our culture, our language, and such.”

Her first book, I Am Not A Number, was on Indian Residential School. Dupuis says Heart Berry Bling talks about something very personal. It’s fictional, about a young Anishinaabe girl Maggie and her grandmother, drawn on Dupuis’ own experiences. She explains how the Indian Act affected her grandmother and in turn, herself.

“In the case of my grandmother Irene Couchie, she lost her status when she married a non-Indigenous man. For many of the women across Canada who were left in that situation, you not only lose your status during that time period up until 1985, but you are no longer able to live or hold property in the First Nation community. You can’t pass on your status to your children, so it wasn’t just women who were affected by this, but also the children.”

Status rights were taken away from 1876 to 1985, says Dupuis. Participation in elections were denied as were access to health and education benefits.

“There’s lots of what we call unfair treatment that exists when we talk about the gender discrimination that exists in the Indian Act. There’s that other side too that if you were a First Nation man, if you married a non-Indigenous woman, that man did not lose his status, but, in fact, that non-Indigenous woman became eligible for status and also band membership. And they could actually then pass it on to their children and grandchildren, etc.,” she explains. “Definitely, when you talk about gender discrimination, it did exist for many, many years. Women in our communities, and children — it still impacts us today. If you think of what was lost and the disconnection over the years.”

Dupuis talks about her new heart-filled story of a little girl named Maggie who goes to visit her granny in the city one fall afternoon. Dupuis’ father and her used to visit Granny every weekend.

Maggie learns about Granny’s past and why she had to move away from her reserve community and leave her family and culture behind. Granny shares how beadwork really helps her. Then Maggie takes up the needle and the strawberry teachings.

“When she’s learning to bead, it’s not just learning about the Indian Act or part of the Indian Act, but it’s also learning about the idea of persistence, too, that not everything comes easy. You have to have patience and work through it.”

Jenny remembers conversations when people were getting their status cards again and photos had to be sent in with applications.

“I remember within my family, my father and my grandmother, I believe there was a sense of thinking about what that would mean for their future, on a lot of different levels, with so many years of being separated and not having that fair treatment and watching other community members. Even in the case of mine, I didn’t receive my status until 2011, where many of my cousins did have it. You live in the community and you engage in the community with family members but you still have that division. The separation exists because of that law from the federal government.”

Dupuis raises questions on what that policy meant to a child’s identity and identity loss as they grew up. For Heart Berry Bling, she thought of where people find Indigenous joy.

“In my case, I learned to bead from other people in the community and from other communities as well where I used to live. I took those teachings and brought them in and came up with this idea.”

Dupuis praised the illustrator Eva Campbell for her watercolour paintings in the book.

“We decided to model a woman like my Granny. I gave photos of my grandmother, the types of clothing she would have worn back in that day, thinking of the eighties with the hair styles.”

Dupuis also had Campbell consider what Granny’s apartment on Duke St. in North Bay used to look like with the couch and the crocheted blanket.

“She was so proud to get this couch with her bingo winnings.”

Heart Berry Bling is on the shelves May 9 and can be pre-ordered.