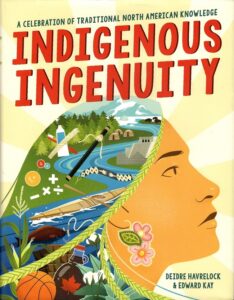

Book review: Indigenous Ingenuity: A Celebration of Traditional North American Knowledge

Deidre Havrelock and Edward Kay’s , designed for young readers, explores Indigenous Science, Technology, Engineering, and Mathematics (STEM) across Turtle Island. The authors’ vision “to celebrate traditional North American Indigenous innovation in science, technology, engineering, and math” is admirably accomplished (4). Across 10 chapters, Havrelock and Kay discuss sustainable land management, transportation, communications, agriculture, hunting, health sciences, textiles, architecture, civil engineering, mathematics, and arts, sports, and recreation. The final chapter offers a listing of efforts of contemporary Indigenous peoples working to restore, regain, and re-vitalize colonized land and waterscapes. Overall, the work represents the accumulation of diverse sets of Indigenous knowledge from the Maya to the Inuit. It will generally serve young audiences well.

The large geographic scale – covering all of Turtle Island – and the time depth – vaguely pre-European – leads to a sense of the authors merely reciting Indigenous accomplishments. I would have loved to have seen a greater discussion of technology spread and diversification. Regardless, parts of the work were interesting, such as the discussion of Maya mathematics. For instance, Havrelock and Kay nicely point out that the Maya were utilizing the concept of zero, long before it became accepted in Christian Europe (179-80). The discussion surrounding textiles, clothing, and fashion was also fascinating. Apparently, Nations that lived on the Plains used buffalo-hair extensions attached by spruce gum to further the long hair aesthetic (124). And, we developed complex clothing from cotton and other natural fibres, including leather for clothing and armour. In health sciences, you will learn that Aztec and Mayan doctors used bird bones to inject medicine and flush wounds (101). Aztec doctors also used urine works as a cleanser of wounds (96) and had the know-how to reattach noses and repair cut lips (97). In fact, many Indigenous medical practices in 1492 were more advanced than European treatments – after all, we never shaved a chicken’s butt to try and cure the plague (87). Unfortunately, the Spanish destroyed many of the Mayan and Aztec medical, mathematical, and other scientific texts. Nonetheless, the biggest and most astonishing fact in the text, for me as an Anishinaabeg, was the surprising revelation that the Haudenosaunee were America’s first democracy (2). Yet, despite Havrelock and Kay’s hyperbole in this instance, plenty of interesting facts and tidbits are found throughout the book.

Despite the book’s many interesting details, I found the scope too generic and broad ranging. It will likely capture children’s minds and interest, most likely in Grade 6 or lower. It does contain some interesting experiments and activities for the classroom or home. Yet, for higher grades, its pages will be helpful solely for adding the odd fact or ‘by-the-way, did you know?’. Do not expect the monograph to offer in-depth explorations of Indigenous STEM. If you want to learn more about Mayan astronomy or Aztec architecture, you need to consult the selected bibliography or limited source notes.

I would recommend this volume be used by grade school teachers looking for a quick source of information on Indigenous STEM, that needs to be supplemented by local Indigenous knowledge. Importantly, no matter how basic or superficial, the book serves as a reminder and a lesson that Indigenous people had incredible people who delved into the world of STEM to create sustainable complex societies and technologies throughout Turtle Island.

Deidre Havrelock and Edward Kay. . New York: Little Brown and Company, 2023.

ISBN: 031641333X