Opinion: Humour is in the eye of the beholder

By Maurice Switzer

The first joke I can ever remember hearing was one told by my grandfather Moses.

It was a sunny Saturday afternoon and about 50 relatives were gathered in someone’s grassy backyard in Alderville First Nation for the Marsden family reunion.

The adults huddled to catch up on one another’s gossip while we kids burnt off some energy racing in burlap sacks, or running precariously while trying to balance raw eggs in spoons.

Before the tables were set with all manner of potluck dishes, it was time for words of greeting and welcome to clan members visiting from as far afield as the southern United States.

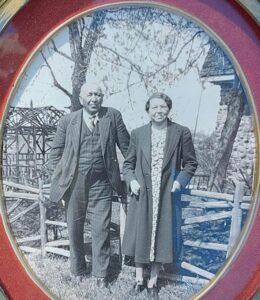

Grandpa Moses’ father was from Hiawatha First Nation on the other side of Rice Lake, but the boy moved back to Alderville to live with his Marsden grandparents after both his birth parents died. He became the community’s elected Chief from 1904-09 and, despite being enfranchised in 1920 and moving with wife Nellie Franklin to Lakefield in 1920, was still regarded as a family patriarch.

Trips to the family reunions were seldom uneventful.

On one occasion, while rounding a corner in the neighbouring hamlet of Hastings, one of the wooden-spoke rear wheels of Grandpa’s Model A Ford spun off in a direction different from the one he intended the car to take. The weight of eight passengers crammed into the roadster kept the car upright, even though it was now perched atop only three wheels.

Grandma improvised, and our branch of the Marsden family adjourned for a makeshift picnic on the nearby shore of the Trent River, thanks to the potluck dishes she had prepared for that afternoon’s Alderville reunion.

Such experiences provided Grandpa Moses with plenty of speaking material when he was called on to address various audiences.

This time, he began his remarks with a story, which all in attendance listened to with bated breath, unsure of whether they were about to hear a weighty family legend, or the sort of anecdote that might be expected from someone with as colourful a past as Grandpa.

“There were two neighbours, whose farms were beside one another,” he began, in a solemn and unwavering voice. “They were friends for years, but one day, the one farmer disappeared. His friend never knew what had become of him…Then, years later, he was out tending to his crops and his old friend appeared, wearing the vestments of a Methodist minister…He was surprised, and wondered what had led to this dramatic change in his neighbour’s circumstances.”

“Well, my friend,” his neighbour recalled. “One day, I was out in my field and I looked up and saw some clouds moving around in the sky until they formed the initials ‘P’ and then ‘C’…I knew this was God’s message that I should Preach Christ. So I went to college, got ordained as a minister, and here I am before you today!”

“His old friend looked pensive, then after a long silence asked: ‘How do you know God didn’t mean Plant Corn?’”

Grandpa’s punchline was greeted by a flood of giggles and guffaws from the assembled adults. The joke’s subtleness may have been lost on some of us younger ones at the time, but these many years later, I can still vividly remember the story and it brings a smile to my face.

Much has been written about the importance of humour to Indigenous peoples. PhD candidates and stand-up comedians have postulated that Indians have used laughter as an antidote to treat the residual impacts of colonialism and genocide.

There may be some truth in that, but Indigenous peoples do not enjoy a monopoly on using humour as a coping mechanism. Fresh memories of six million lives lost in a 20th Century Holocaust has not prevented Jewish comedians from dominating that field of entertainment. Humorist Mel Brooks composed the spoofy sendup, “Springtime for Hitler’, for a hit Broadway musical.

What makes people laugh can vary widely, but there are some common elements across cultures, genders, and age groups. There are exceptions, of course, but most people tend to enjoy laughing at situations with which they can identify, but that do not poke fun at or mock the misfortunes of others.

No-one is harmed by comic Don Burnstick’s famous series of “redskin” jokes. “If you know how to fillet baloney, you might be a redskin!”

There’s no pointed personal attack intended when someone quips: “If you prepare a spirit plate at McDonald’s, you might be a Pretendian!”

But humour is definitely in the eye of the beholder.

The first time I took my late mother to see a Drew Hayden Taylor play – the premiere of “Baby Blues” in Peterborough’s Market Hall – she complained that the story made fun of Indians. The Curve Lake First Nation author/playwright has built a career on telling stories that use his particular brand of humour to examine Indigenous realities.

“You cannot be Indigenous without having a sense of humour,” he insisted to CBC interviewer Rosanna Deerchild.

That may be the case for most human beings, but all the best storytellers who rely on humour to make their points – including Grandpa Moses – need to bear in mind that it helps if their audience is clear about whom exactly the joke is on.

Maurice Switzer serves on the board of the North Bay Indigenous Friendship Centre.