First Nation writers capture literary awards

By Sam Laskaris

ANISHINABEK NATION TERRITORY – A book that helps introduce children to the Anishinaabemowin language is among those that have been recognized with a prestigious literary prize.

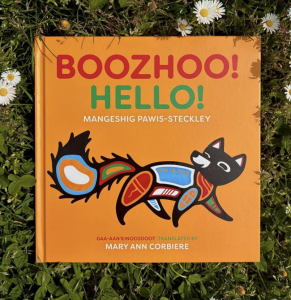

Boozhoo! Hello!, written by Mangeshig Pawis-Steckley, a member of Wasauksing First Nation, was selected as the top book in the Children’s Category for this year’s First Nations Communities READ Indigenous Literature Awards.

Meanwhile, The Baby Train, written by Mi’kmaq descendant Stella Shepard, who is connected to Benoit First Nation in Newfoundland, was declared the winner in the Young Adult/Adults Category.

Boozhoo! Hello! is written in both English and Anishinaabemowin and describes sights and sounds of various creatures, including bees buzzing, minnows dancing, and a fox digging.

The Baby Train is about the former Canadian hospital practice in which unwed mothers, including Indigenous ones, would have their newborns taken from them at hospitals and ‘sold’ to American couples.

Both Pawis-Steckley and Shepard received $5,000 each for their awards, announced by the Periodical Marketers of Canada and supported by the Ontario Library Service.

Pawis-Steckley, who has lived in East Vancouver for the past decade, was obviously thrilled with his award.

“It’s honestly a huge honour,” he said. “I think there’s just so much love and hard work that went into this book from everyone involved. And just to have it be recognized by Indigenous librarians and the community really speaks a lot to what this book came to be.”

Pawis-Steckley said his book is beneficial to others.

“It’s a really great way to introduce our language to our youth,” he said. “It’s a fun way to do that. And that was really the main goal of the book.”

Pawis-Steckley said he was inspired to write the book by his daughter Mino-Margaret, who is now three.

“It all started with her when she was born,” he said. “I did the illustrations. I started drawing them in black and white because when kids are first born, they’re really drawn to those high contrast of black and white images… As she grew older, I coloured them in and thought this would make a really great book. I decided to add a bit of text to it.”

He then approached a publisher, Groundwood Books, to pitch his book.

“They loved the idea and wanted to pursue it further,” he said. “So, we added, I think, about eight more illustrations to make it a full book.”

Shepard said she was surprised to win her category but added, “it was amazing and very humbling.”

She added that she hesitated a bit when her publisher, Acorn Press, approached her for permission to nominate the book.

“I was thinking I would not be shortlisted,” she said. “And then when I learned my novel was selected, I was just really dumbfounded. It’s just totally a privilege.”

Shepard added that simply getting her book published was a feat in itself.

“You have to go through the long waits, the edits, waiting for a response from emails to the publisher,” she said. “That in itself is time-consuming. And if you can get published, that in itself is good.”

Shepard currently lives in the rural Prince Edward Island community of Morell.

“To write from such an isolated place and to win a prestigious award is truly a gift,” she said.

Shepard said she wrote The Baby Train to honour unwed mothers like herself and the injustices they faced.

“Our babies were taken and adopted to mostly wealthy American families,” she said. “I was very fortunate I was able to keep my baby, although I almost lost him in the delivery room.”

The birth alert system marginalized vulnerable and young unmarried women. It allowed hospital staff to notify child welfare authorities about expectant mothers they deemed at risk.

Shepard said when she gave birth to her son in the 1970s, a nurse walked away with him.

“The doctor intervened and took my baby from the nurse and gave him back to me,” she said. “To this day, I still have nightmares. But I didn’t realize at the time what she was planning to do was take him to the nursery and out the back door at the hospital to a foster home where he would have stayed until adopted out, probably to an American couple.”