Remembering Beausoleil’s Spanish Flu Epidemic of 1918

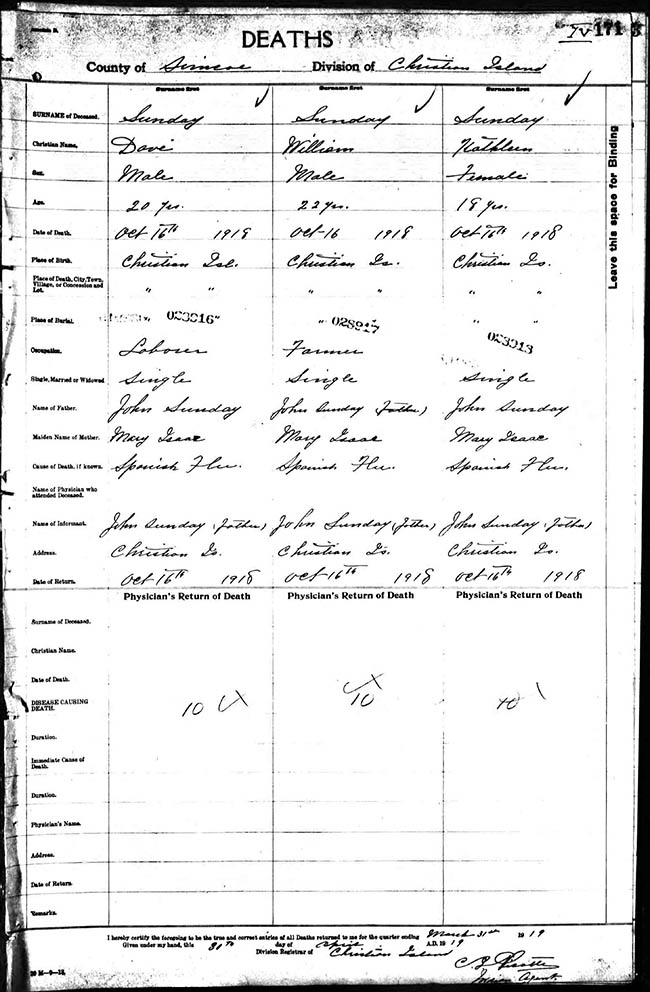

BEAUSOLEIL FIRST NATION — Any parent would grieve at the loss of their child, but on October 16, 1918 John Sunday had to say goodbye to three of them. Willie, 22, Dave, 20 and Kathleen, 18 had lived their entire short lives on Christian Island. Willie, like his dad, was a farmer, Kathleen helped her mom care for her four younger siblings and Dave worked outside of the home as a labourer.

John was only 52 and a father of eight when he was given the heartbreaking task of reporting his children’s deaths to the authorities. He did not need the local physician, Dr. Sinclair, to confirm what had killed them because he was witnessing the virus sweeping through his community at a horrifying rate: Only the day before Jerry Monague had lost his two sons, Edward and Jonas, themselves leaving young families behind. This second onslaught of Spanish Influenza had mutated to become deadlier and more virulent than the wave that came in the spring. And it brought with it terrifying and excruciatingly painful symptoms: The contagion announced itself through extreme fatigue accompanied by a high fever and headache. Those in the thick of the virus had their bodies wracked with violent coughs and struggled to breathe as their lungs filled with fluid. With little or no air in their bodies, the victims’ skin turned blue, blood foamed from their mouths and sometimes from ears and noses. An individual could be fine one minute and within hours, succumb to its horrors. Strangely, it attacked young adults, usually between the ages of 20 and 40.

Researchers are uncertain where the virus originated but most experts believe it started in either the United States or France. It is called the Spanish Flu because Spain, which remained neutral during the war and thus free from censorship, was the first country to publically report its existence.

The flu pandemic had an apocalyptic effect upon the world’s population in general. One actuarial report claimed, “Nowhere in the history of public health is there a record of so sudden, so severe and so extensive a loss of life within a few months.” The document continued, “Within a few months the influenza and its pneumonic complications destroyed more lives throughout the world than did four years of the Great War.” The disease touched all levels of society, but the poorest or those in areas lacking immediate and proper health care were hardest hit. Given the living conditions on First Nations’ Territories during this time, it is not surprising that Duncan Campbell Scott, the Deputy Superintendent General wrote in his Annual report that the Indians of Ontario “suffered very severely from the epidemic”.

Beausoleil Island First Nation was affected more than most. In a single month, October 1918, the community lost 47 individuals to the virus, most of them being in their early ‘twenties. Using statistics we get an idea of the huge impact this virus had upon the island. The 1917 Indian Department Census reported a band membership of 317. Losing 47 individuals the following year represented a loss of 15% of its population. As it was for the Monague and Sunday families, the year 1918 was a very hard one for the island community in general. Looking at the tally of deaths for this single year, the total population of Christian Island was reduced by almost 19%, meaning that nearly one in five individuals died. The world average for deaths due to the pandemic was one person in 18.

The war ended in less than a month after John Sunday’s children were laid to rest. Some scholars believe that the Spanish influenza pandemic hastened peace talks, as both sides were experiencing heavy losses on the home front as well as in the trenches. In all, 4,000 First Nations people enlisted in the Canadian Expeditionary Forces and many of those lucky ones who survived found the joy of their homecoming diminished by the loss of their loved ones, those brothers and sisters, parents and sweethearts who were taken in the prime of their lives by this devastating virus.